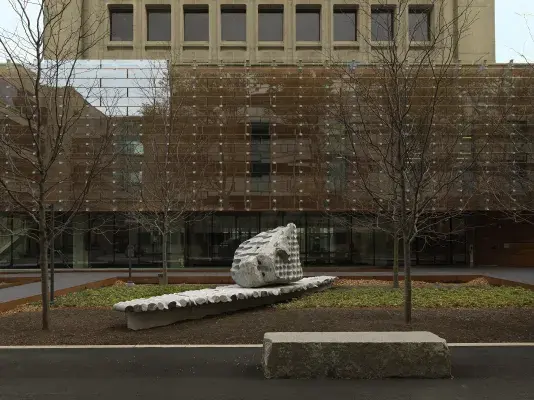

Julian Charrière, Not All Who Wander Are Lost, 2019/2023. Commissioned with MIT Percent-for-Art funds and a generous gift from Robert Sanders (‘64) & Sara-Ann Sanders. Photo: Dario Lasagni

Not All Who Wander Are Lost, 2019/2023

Much of Julian Charrière’s work is concerned with how humans have represented and interacted with the natural world. “A recurring question in my work,” he has said, “is how that relationship changes—how our ideas of what constitutes as nature and the natural world are cultivated and transfigured.”

In many of his projects, culturally and historically specific ways of representing nature—for instance, the landscapes of German Romanticism—are entangled with the vastness of planetary time. These timescales are juxtaposed in his sculptures and installations, which often employ scale to create a sense of the geological sublime.

Not All Who Wander Are Lost (2019/2023) consists of three boulders, each resting on a row of stone and metal cylinders. The boulders are glacial erratics, rocks transported over long distances by glaciers, and because they differ from local bedrock, they help scientists trace the trajectories of long-melted glaciers. Their name derives from the Latin word errare, meaning “to wander.” At MIT, two erratics can be found embedded in the building’s landscaping, and one sits on a second-floor terrace, as if it had been deposited there by a vast, ancient force.

These boulders are not left to stand intact in Charrière’s work. They are densely perforated and sit atop their own extractions. These cylinders of stone, patched with metals, mimic the form of core samples often taken from deep inside the earth. Exploratory core drilling is used to facilitate the extraction of oil, gas, coal, ore, and minerals, and core samples are also used by geologists to study the history of the planet. The sculptures’ honeycomb quality further echoes the optimization of extraction: more hole than substance, the works are poetic illustrations of how even the most enduring, solid forms can be brought to near collapse.

By placing the erratics atop their cores, Charrière evokes both human and nonhuman histories of movement, and he invites viewers to wonder how heavy objects like boulders might have traveled before the advent of the wheel or the container ship. Seeing their transformation into sculptures, we are reminded that these boulders are among unfamiliar bedrock once again—this time moved not by glaciers but by quarry machines, modern logistics, and the hand of the artist.

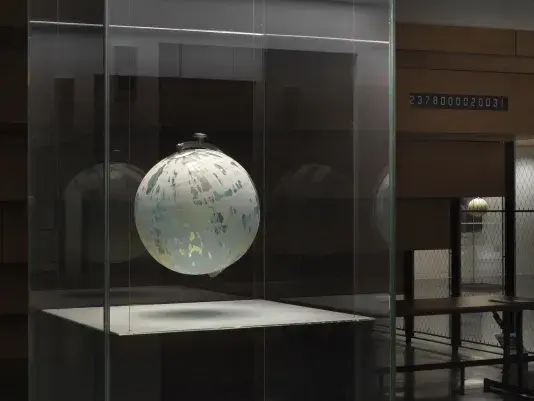

Not All Who Wander Are Lost forms part of Charrière’s three-part commission for the new Tina and Hamid Moghadam Building at MIT, collectively titled Everything Was Forever Until It Was No More (2023), which includes We Are All Astronauts (2013/2023) and Pure Waste (2021/2023).

Julian Charrière (b. 1987) was born in Morges, Switzerland and lives in Berlin. His work examines the representation and perception of the natural world in an age of planetary ecological change. He studied with the artist Olafur Eliasson as a participant in his Institut für Raumexperimente (Institute for Spatial Experiments) at the Berlin University of the Arts. His work has been exhibited at institutions across the world, including solo presentations at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Langen Foundation, Neuss, Germany, Dallas Museum of Art, Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Italy, Berlinische Galerie, and Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne, Switzerland, among others.