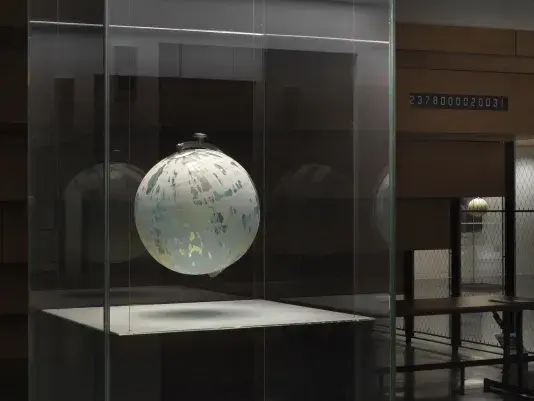

Julian Charrière, Pure Waste, 2021/2023. Synthetic diamond produced with atmospheric carbon collected through direct air capture technology. Commissioned with MIT Percent-for-Art funds and a generous gift from Robert Sanders (‘64) & Sara-Ann Sanders. Courtesy MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Photo: Dario Lasagni

Pure Waste, 2021/2023

Julian Charrière’s work is concerned with how humans have represented and interacted with nature. “A recurring question in my work,” he has said, “is how that relationship changes—how our ideas of what constitutes as nature and the natural world are cultivated and transfigured. Many of my projects explore the entanglement itself and the reciprocity between human time and geological time.”

Pure Waste (2021/2023) consists of a small synthetic diamond dropped into the foundation of the Tina and Hamid Moghadam Building (Building 55) during its construction. The diamond’s location is indicated by a small circular irregularity in the concrete floor. The carbon molecules used to make this diamond were drawn from a novel form of atmospheric carbon capture, effectively “mining the sky” above the ice cap, as well as from the exhalations of human volunteers, including MIT scientists and staff who work in the building. Atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, have risen precipitously since the Industrial Revolution, threatening the future of life on the planet. While carbon dioxide is produced by combusting coal and oil, it is also released by the respiration of humans and other animals. Pure Waste, then, might be conceived as a breath crystallized within the building—a breath drawn in and held.

Although the work shares a title with a film by Charrière (in which the artist traverses thelandscapes of northern Greenland to deposit five “sky diamonds” into a glacier mill in the polar ice cap), the work commissioned for MIT is conceived in relation to the tradition of builders’ rites and ceremonies dating back to ancient times. Often, items of significance, such as coins or newspapers, are placed within the foundation of a building during its construction. In some cultures, living beings were once entombed beneath foundation stones, a history that is faintly echoed in Charrière’s sequestration of human breath. By drawing on these practices, the artist both consecrates the structure and gestures toward the sacrifice at its foundation (perhaps even including the carbon emitted duringthe building’s construction).

Pure Waste, then, offers a reminder of the elemental material that has circulated between organic and inorganic realms since the beginning of life on earth. “We are the atmosphere, and the atmosphere is us,” it affirms. At the same time, the artwork temporarily removes a minuscule fraction of this material from circulation—as long as the building is standing, this carbon will remain inert. Charrière’s work is ultimately a tiny gesture of repair: rather than mining carbon and releasing it into the atmosphere as emissions, Charrière brings the sky down to earth as a poetic inversion of extraction. Hisintervention resonates with recent calls by climate activists to “keep it in the ground”—that is, to leave known reserves of fossil fuels untouched rather than extract them for combustion.

Pure Waste forms part of Charrière’s three-part commission for the new Tina and Hamid Moghadam Building at MIT, collectively titled Everything Was Forever Until It Was No More (2023), which includes Not All Who Wander Are Lost (2019/2023) and We Are All Astronauts (2013/2023).

Julian Charrière (b. 1987) was born in Morges, Switzerland and lives in Berlin. His work examines the representation and perception of the natural world in an age of planetary ecological change. He studied with the artist Olafur Eliasson as a participant in his Institut für Raumexperimente (Institute for Spatial Experiments) at the Berlin University of the Arts. His work has been exhibited at institutions across the world, including solo presentations at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Langen Foundation, Neuss, Germany, Dallas Museum of Art, Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Italy, Berlinische Galerie, and Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne, Switzerland, among others.